“I have fallen…”, the white poor in South Africa

This project, made between 2002 and 2006 looked for answers to the questions: What is poverty? And what is its relationship to race? White poverty is not new, or specific to South Africa. Yet perceptions of who can or cannot be poor (or rich) persist in the mind of many of their citizens. In a country where the gap between rich and poor is ever-increasing, and having been deprived of some of their privileges like job reservation, and extensive state support, the white poor must seek ways to adapt or at least survive.

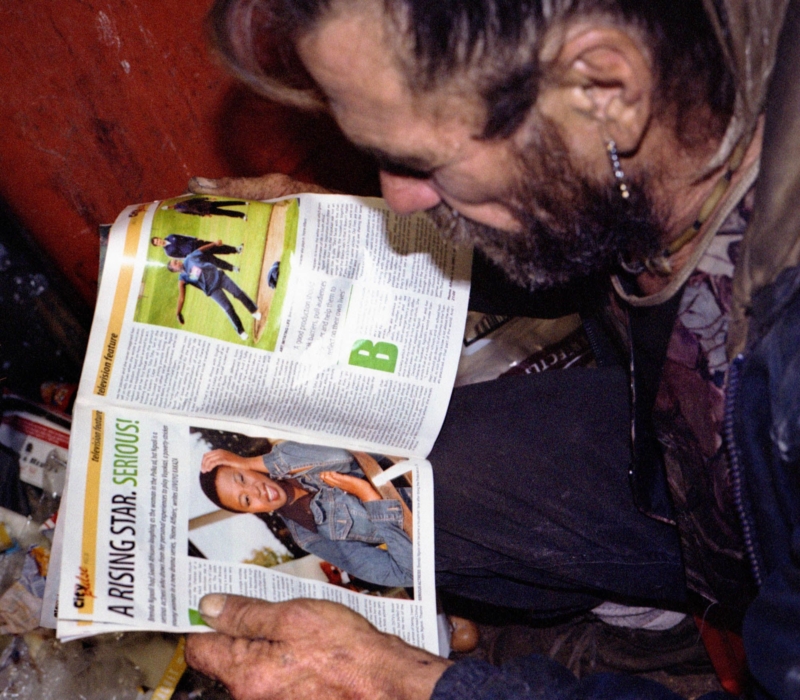

Giant knobbled hands, black with dirt, bring a large crumpled sheet of plastic, once used to wrap chicken, smelling of rancid meat to his mouth, biting off the barcode sticker, he smoothes and folds the plastic into a neat bundle. Sheet after sheet is processed, he doesn’t react to the stench – he doesn’t even smell it.

“I get a good rate at the recycling centre, they can trust that I bring clean plastic,” says Gerhard Vermaak.

Nicknamed Satan by his neighbours, “because of this”, he points to a snake pendant necklace around his neck but perhaps more because of his intimidating presence, his long hair tied in a ponytail, lack of social graces and that he has his own squatter camp under a clump of blue gum trees in the middle of Danville, a historically poor whites area stuck between industrial west Pretoria and Atteridgeville.

While South Africa has deprived poor whites of their previously “privileged” position, they are now seeking ways to adapt, or at least survive. But for some the statement, “I may be poor but at least I’m still white,” no longer holds any water. While many would not know class theory from a hole in the floor, South Africa’s poor whites are at last living the reality they were sheltered from for decades.

When the armblanke fled their sharecropper holdings after the Anglo Boer war, agricultural crises and during the 1930’s Depression and streamed into the cities looking for work for many their first home were in the multiracial slums that had sprung up informally around industrial centres. The elite saw the possibility of these poor whites developing class-consciousness and joining a multiracial class struggle against the elite as detrimental to the developing Afrikaner capitalism. With a quarter of Afrikaners living in absolute poverty, the elite made them the cause of Afrikaner nationalism.

“A potentially harmful working class would become more manageable if integrated with the white middle class, and turned into a productive labour force,” says Annika Teppo, a Finnish anthropologist who did a doctoral thesis on the rehabilitation of poor whites.

“The existence of poor whites represented a racial weakness and an illness of the social body,” Teppo states. Through optimal social and economic conditions they could be guided into becoming, what Teppo calls, “a good white”.

They provided them with jobs through job reservation and ensured that no skilled blacks could advance ahead of them, protected their unions, provided welfare support, housing schemes and social grants.

Eventually every big city had it’s poor white council house township, like Jan Hofmeyer and Danville as a buffer zone near industrial areas and the outlaying black locations. Decent housing built around parks and supervised recreation facilities under the careful eyes of social workers, poor whites were meant to be given a leg up the class ladder to attain middle-class.

But with more and more whites standing a robots today, it is evident that not all whites were rescued from poverty. “In the context of the prosperity of whites under apartheid, being white and poor therefore implied being marked in a particular way, as a carrier of a form of deviance,” says sociologist Irma Du Plessis, of Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research. “The very notion of .poor whites was seen as an aberration and therefore couched in the language of disease and contamination.” Similar to stereotypes of Jerry Springer type American white trash, the white poor were morally deficient, stupid, fat, lazy, drug addicted drunks and pathetic misanthropes who were “a waste of white skin.”

As Apartheid’s political control and rapid economic development accumulated wealth for white South Africans, poor whites became a minority and were no longer used as a rallying point. By the 1970’s the policies of the National Party shifted and poor whites were increasingly abandoned by the state as the NP identified more with middle-class white collar workers and the pursuit of a more capitalist agenda. In 1973, after crippling strikes, the government effectively ended job reservation by announcing that blacks could do skilled work in white areas.

The dawn of democracy accelerated the downward slide of whites without capital or marketable skills. Steps to broaden access to social services removed the extensive state support for poor whites. Liberalisation and privatisation of the economy ended their predominance of the state and parastatal industries. Guaranteed jobs before, many of these workers never supplemented their training by studying at trade colleges to get certification. Now having to compete in a globalised world, they are most vulnerable to job losses.

“Poverty in South Africa no longer has an exclusively black face, it is becoming less of a racial problem and more of a South African problem. More and more white people are joining the ranks of the poor on a daily basis,” says Lullu Krugel, economist with trade union Solidarity. Quoting various researches from the Bureau of Market Research, Statistics South Africa and HSRC, she concludes that “1 in 10 whites are living in absolute poverty.”

Using scrap metal, wood and a few precious tarps and cardboard, Vermaak has constructed what we are familiar with only in poor black areas, mkukhu’s. Living in his compound is his wife, Helen, step-daughter, a white couple renting a caravan and 3 black families to whom he rents shacks. Surrounding the shacks are decaying sofa’s and piles of rubbish, the only thing distinguishing it from a dumpsite is that all the rubbish is sorted: cardboard, plastic, glass and metal.

Sleeping there one night on a bed on the stoep of the daughter’s shack with no locks, no bars, no doors and no fences, just a tattered grass blind between me and the world reveals the vulnerability of how they live, almost safe because they have no real valuable possessions, but feared because they wear their poverty so openly.

Ironically Vermaak does not see himself as destitute. “I’m not poor, if you’re poor you don’t do anything… I am a businessman; I rent the shacks for R40, the caravan for R100 sell chickens for R20, and sell stuff for recycling.” On average it takes three months to collect a decent amount of trash of each category which he can earn about R300 each, “It depends on my luck, sometimes it can take 6 months to get enough to sell.” His wife receives a disability grant of R700 per month and they often survive on food packages filled with dated Woolies food.

Vermaak used to work as a bricklayer but now “without paper’s I can’t get work, and if do get something, they won’t pay me properly, less than R1000 a month, and then still work you like a slave… I’d rather do this. I’m my own boss.”

Grabbing the handle of his grandly titled “Service provider to Mondi Recycling Waste Paper Dealer” trolley he heads off on the dark road in search of valuable refuse.

His most fertile gathering ground is the OK bazaars in the centre of Danville, arriving at 7 at night he waits ‘til closing time at 8.30 to start basic sorting out the boxes and plastics. Ripping off staples and stickers, folding them into smaller piles. Later he will sweep the parking lot and bin area. The well-to-do OK owners respect the work he is doing, “No one is allowed to call him Satan here. He does a good job.” They pay him with a loaf or 2 of bread and a frozen braai pack of meat.

Vermaak’s most prized possession is a 1970’s Dodge bakkie sitting on bricks that he’s trying to repair so he can range his foraging further. “If I can fix my bakkie, I can make enough money to buy a piece of land and build a house on it,” he says optimistically.

Travelling through the Daspoort tunnel you get to neighbouring Booysens. There are many people living in desperate situations and you may never know it unless you knew what you were looking for. Behind their pre-fab walls, Pretoria west houses have large yard’s and most have ‘Wendy houses’, wooden garden sheds, filled with families. Most are without electricity and have no water or toilet facilities. They must use the toilet inside the main house. For most allowing a family to squat on their properties is a cash business.

Attie De Vos (42) was living in one such “shack farm” paying R1200 for a room. There were 6 other crudely built rooms with rentals of between R800 and R1000. Unable to continue paying such rents, De Vos and his common law wife Kathleen and two children Roeleen and Thea-lize now live as backyard dwellers in a blue canvas tent divided into rooms by net curtains. Outside the tent De Vos is building a shack with wooden pallets salvaged from Coca-Cola. “I can’t finish it now, we pay R300 rent, the people we’re renting from can’t afford their own rent and now they’ve given notice. I don’t know if we can stay.”

Describing his situation De Vos says “Ek het geval,” (I have fallen). De Vos was a beneficiary of the Nationalist employment policy. After doing his national service he was employed on the railways as a boilermaker, he eventually worked himself into a permanent job working for the Pretoria City Council. “I even bought my own house.” Then when employment equity was introduced he was forced into voluntary retrenchment. “I lost my house, and then my (previous) marriage was gone.”

“I started selling vegetables off my bakkie to survive” He has since lost the bakkie as he fell further.

Now he works as a smouse (hawker), making firelighters of his own invention, a secret formula of petrol, styrofoam and plastic that even burns in water that he sells for R20 a bottle, working 7 days a week, his skin baked to copper from his time on the road.

“Living in the tent, every time I come from work, it’s like I’m on holiday,” he laughs. But he doesn’t make enough to properly feed his family. Every Wednesday, Kathleen goes across the road to receive a food parcel from Eleŏs community centre, a job creation project and feeding scheme supported by churches and charities. Kathleen speaking to a woman who acts as a mentor, finds out she pays her black maid R60 a day, and asks if she can’t rather come and work for her, the woman curtly says, “No, it’s not work for a white person.”

Too poor to afford deposits on formal accommodation but too scared to squat, many do what they can to pay rent, even if it means not being able to afford food. “There are 59 soup kitchens and feeding schemes in the Moot (Danville, Booysens and surrounds),” says Dr Dawie Theron of Helping Hand, the charity wing of Solidarity.

De Vos still has fighting spirit “If things go on like this, I’m going to take all my pallets and build a house across the road in the veld. Then they must come lock me up or chase me away.”

A few hundred metres away from their tent, across the bulldozed stretch of veld, Frikkie Botha (29) lives with a friend in a sloot – a concrete storm drain under the Mabopane Highway. Frikkie moved in with his friend 3 months before. They live 20 metres into the drain. Frikkie’s bed is a damp mattress. Looking much like a gothic teenage boy’s room there are water stained magazine cut-outs of Afrikaans poppies, and charcoal scratchings of the names of various previous inhabitants, swear words and crude drawings of women graffiti the walls.

“I live here because my father and mother are suffering. They only sell the Rapport & mother only gets disability pension for epilepsy. They can’t look after me.”.

Frikkie left remedial school at 16, “I got bored… and wanted to help my parents make money.” So he worked pushing trolleys at the nearby Quagga shopping centre, then as a newspaper vendor. He also periodically gets a “proper” job but can’t keep it.

Frikkie’s mother, Annetjie, and father, Nico, work every Sunday as Rapport newspaper vendors. At 2 o’clock in the morning they leave home to walk to a pick up point for a delivery truck at 3. They pile in with dozens of other poor-whites from the area and are taken to the depot near Danville. While trucks are loaded with newspapers and vendors, they wait grateful for the job, in the bitter cold to leave just before 5 am. For many in the Moot region selling the Rapport is the only job they can get and according to a depot supervisor, it is a poverty alleviation project of the newspaper. These vendors receive about 25 percent of each newspaper sold.

As the sun rises, Annetjie Botha is the last drop off. Standing on a intersection on a quiet Sunday morning she stands stoically clutching a pile of newspapers. Keeping an eye out for the traffic flow, she crosses the road constantly, angling for a better position. She made R200 that day but sometimes only makes R80.They pay R600 for a tin shack at the back of a house. For a month Frikkie also lived there but left when he couldn’t afford to pay R400 for a mattress, cordoned off by curtains, in a garage shared with 6 others. He has since moved back to the sloot.

His mother, crying, despairs at how the family fell into such a circumstance, how her son ‘lives in a hole’. “I have been trying to get a house from the municipality since 1998. Despite what I’ve been through I am going to stand up for my rights. Everyone steps on me. I have reached breaking point. I want no more nonsense. Even if I must go see them (the housing department) every day, and make them mad, I want a house… Klaar. People think that only black people are poor in this country, they must come and see how we live.”